Idhika Agarwal

Introduction

The internet, which was once only limited to exchanging emails in the early 1960s, now caters to multiple needs of the people. The advent of Wi-Fi and mobile data has made the internet much more accessible to the common people, thereby increasing the commercial activities and flow of data from one person to another.

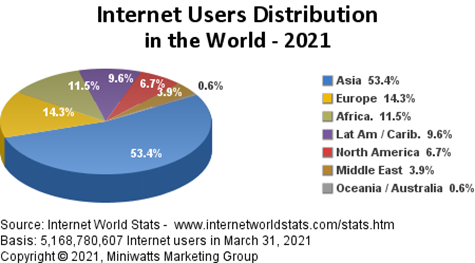

The number of people using the internet is increasing by each passing minute. The pandemic has certainly contributed a great deal to the same. 65.6% of the global population[i] was recorded to be using the internet as on March 2021.

Due to the same, a lot of businesses have shifted their operations to online platforms. This results in a situation where both the parties of a transaction may be located in different continents[ii] and the dispute resolution, in today’s time will not be confined to the geographical boundaries of a country.[iii]

With the Intellectual Property Laws being recognized, the advent to computer programs (TRIPS Agreement, 1994)[iv] and domain names, it becomes imperative to analyze the jurisdiction of the disputes happening over cyberspace as they have multi-jurisdictional character. Thus, this blog discusses the question of jurisdiction in internet disputes concerning Intellectual Property Rights in the Indian backdrop

Indian Approach

To begin with, the single judge bench in Casio India v. Ashita Teleservices[v] dealt with a trademark dispute between the plaintiff being a subsidiary of Casio headquartered in Japan and the defendant being situated in Bombay. The High court reiterated the fact that content over the internet can be accessed from anywhere and it shall not be reasonable to confine the territorial jurisdiction to the place of residence of the defendant like in the usual civil procedure codes.[vi] Thus, this case gave jurisdictional recognition to all the places from which the websites could be accessed from and allowed courts from the user’s forum state to invoke their jurisdiction for cyberspace matters.

On the contrary, the single judge bench of Delhi in the case of India TV Independent News Service v. India Broadcast Live[vii] scrapped the equation of accessibility of the website to jurisdiction. Thus, the mere availability of the website in Delhi cannot entitle the court to invoke ‘personal jurisdiction’ against a defendant from Arizona. The court instead considered the ‘level of interactivity’ of the website as well as the probable ‘effect’ of the website as a factor when determining jurisdiction. However, this case could not overrule the Casio India case since both were adjudicated by a single judge bench.

To settle the position of IP disputes over the internet in India, the Banyan Tree Holding v. Murali Krishna Reddy case[viii], was the need of the hour.It overruled the Casio judgement and upheld the India TV case. In this case, the plaintiff was located in Singapore whereas the defendant was situated in Hyderabad. The plaintiff claimed that the service mark ‘Banyan Tree’ was being used by them extensively and continuously, and had acquired a secondary meaning. The plaintiff argued that the use of the mark by the defendants was deceptively similar so it unduly enriched from the reputation and goodwill of the plaintiff.

The Delhi High Court in this case had to determine whether it had jurisdiction on the following grounds:

- In what situations will the court have jurisdiction if the defendant operates a universally accessible website and the plaintiff is a non-resident

- Burden of the plaintiff to establish the jurisdiction of the forum state.

Since Section 134(2) of the Trademark Act[ix] is not applicable to the given case, owing to the residency of the plaintiff, 2 significant tests were used by the court in arriving at a determination. They were as follows:

- Effect Test: Plaintiff needs to show that there was a voluntary ‘targeting’ of the users of a particular territory or that there was some injury suffered by the users of the forum state. In other words, if the website operators

- intentionally chose to operate in the forum state, or

- ‘specifically, targeted’ the users of a forum state in order to affect them in any manner possible, the court shall be entitled to invoke its jurisdiction for the said matter

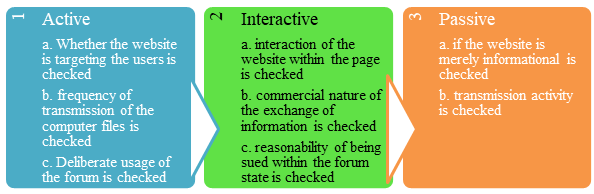

- Sliding Scale Test: as mentioned in the Zippo Manufacturing case[x], each matter before the court needs to be fitted in a scale ranging of:

Thus, in case of a dispute, any website, irrespective of its geographical reach of accessibility, shall be subject to the jurisdiction of the land where it is interactive and its affected target audiences lie.

Analysis and Suggestions

The Contract Act and the Civil Procedure Code are really old pieces of legislation, whereas the Internet and allied concepts are fairly new. In such a backdrop, law needs to be dynamic, and the older laws cannot be applied ipso facto to the facts today. Thus, they could not account for any lacunae in the IT domain.

The judiciary, in light of this, faces difficulties in administering justice and so has relied on creative interpretation of existing laws.

Furthermore, parties can help themselves for deciding jurisdiction by taking precaution at the time of preparing the agreement. Taking inspiration from Section 28 of the Contract Act[xi], the parties, while entering into contract can provide themselves with a sense of certainty and security by binding themselves in the following two manners[xii]:

- Choice of Forum- They can choose a neutral forum or any pre-decided location that they wish to be subject to, in case a dispute arises.

- Choice of Law- due to the multijurisdictional nature of the internet, the parties can also choose to be bound by a certain law of a specific location.

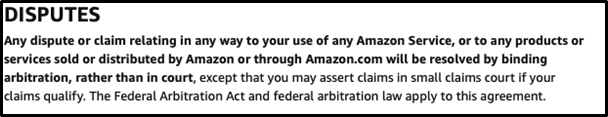

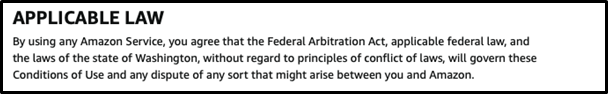

For instance: The User Agreement of Amazon mentions the following:

Figure 1 Source: https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html?nodeId=508088&ref_=footer_cou

Figure 2: Source https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html?nodeId=508088&ref_=footer_cou

Thus, the all e-commerce giants as well as individuals who enter into a contract via the internet shall either bind themselves to a location or the law, or both to ensure that the dispute resolution is smooth.

As an alternate, there needs to be a uniform law[xiii] that determines whether the law of the country of origin of the website or the law of the user’s country or both will be applicable to any cyberspace dispute. There is also an opinion that the cyberspace should have a separate law and jurisdiction[xiv] exclusive to the nature of disputes.

Conclusion

In the light of the abovementioned observations, it is now established in USA as well as India that the jurisdiction of disputes arising over the internet are determined based on the:

- Effect Test, and

- Sliding Scale (Active/ Passive) Test

Thus, in the absence of any uniform law to govern the cyberspace transactions, and based on the landmark judgments of Zippo Manufacturing Co. v. Zippo Dot Com Inc[xv], Darby v. Compagnie Nationale[xvi] and International Shoe Co. v. the State of Washington[xvii] (USA) and Banyan Tree Holding (India) the court determines whether it is entitled to invoke its ‘personal jurisdiction’ against the non-resident defendant or not. To conclude, I would like to state that by laying down certain principles, the court has absolved itself of a very momentary and temporary liability. Technology is ever advancing and in no time these tests might become less effective. Thus, the need to discuss the jurisdiction of internet disputes has not subsided. In my opinion, it should be discussed as widely as the issues of privacy in today’s time. Furthermore, supreme laws like European Union-General Data Protection Regulation[xviii] and its corollaries that deal with E-Commerce and privacy regulations should attempt to incorporate a unified law such that the parties to the suit have a sense of certainty, which is the most basic facet of law. This would be the only remedy to achieve a hassle-free dispute resolution.

[i] Minwatts Marketing Group, Internet World Stats, 2021, available at https://www.internetworldstats.com/stats.htm.

[ii] Peter Swire, Elephants and Mice revisted: Law and Choice of Law on the Internet, University of Pennsylvania Law Review, Vol. 153 1975.

[iii] Micheal Gray, Applying Nuisance Laws to Internet Obscenity, Vol. 6, (No. 2,) | Journal of Law and Policy for the Information Society, p. 317 (Summer 2010).

[iv] Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, 1994.

[v] Casio India Co. Ltd v. Ashita Teleservices Pvt LTD, 2003 (27) P.T.C (Del).

[vi] Rakesh Kumar and Ajay Bhupen Jaiswal, Cyber Laws 64 (APH Publishing Corporation, New Delhi, 2011).

[vii] India TV Independent News Service Pvt. Ltd. v. India Broadcast Live LLC, 2007 (35) PTC 177 (Del).

[viii] Banyan Tree Holding Ltd. v. Murali Krishna Reddy, 2010 (42) PTC 361 (Del).

[ix] Trademark Act, 1999, Section 134.

[x] Zippo Manufacturing Company. v. Zippo Dot. Com. Incorporation (W.D. Pa. 1997) .

[xi] Indian Contract Act, 1882, Section 28.

[xii] Joshika Thappa, Jurisdictional Issues in Cross border e- Commerce Disputes: A Critical Study, Sikkim University, 2018.

[xiii] Gerald Ferrera, Cyberlaw: Texts and cases, Boston College Universities Libraries, ISBN: 0-324-16488-2,

2004.

[xiv] David J and David P, Law and Borders- The Rise of Law in Cyberspace, Stanford Law Review, Vol. 48, No.5 (May 1996).

[xv] Zippo Manufacturing Company. v. Zippo Dot. Com. Incorporation (W.D. Pa. 1997) .

[xvi] Darby v. Compagnie Nationale Air France, 769 F. Supp. 1255, 1262 (S.D.N.Y.1991).

[xvii] International Shoe Co. v. Washington, 326 U.S. 316 (1945).

[xviii] European Union- General Data Protection Regulation, 2016.